VPs (King and Servant)

Note: This is a bit of a longer section. Go through it in small parts if you need to, but it's super important to understand if you want to keep your sanity in learning Pashto. This will help you understand past tense etc.

In the last section we learned how to build phrases using equatives. Now we are going to learn how to make VPs (verb phrases). VPs are ... wait for it ... phrases that are made with verbs. Verbs are words that describe actions, activities, or occurances.

For example, if I say:

This is a VP built with the verb خوړل - khoRul (to eat).

As we explain VPs we'll also learn about what the "king" and "servant" of these phrases are.

3 VP Structures

Pashto learners often get very confused while because there are three different ways for how VPs fit together, depending on what type of verb we have.

- with intransitive verbs

- with non-past transitive verbs

- with past-tense transitive verbs

Depending on what kind of verb you're using, the sentence structure will completely change. If you're used to speaking a language (like most) where the sentence structure never changes this will seem a little insane at first! But don't worry, once you understand what these three structures are it will all make sense and your brain will get used to them with a lot of practice.

1. With intransitive verbs 🛴

Intransitive verbs are verbs that don't have an object. For example, the verbs:

- تلل - tlul (to go)

- راتلل - raatlul (to come)

- رسېدل - rasedul (to arrive)

- غورځېدل - ghwurdzedul (to fall)

...don't involve doing something to an object, they just involve I subject that's moving or experiencing something. For example زه راځم - zu raadzúm (I am coming). There's no object, only a subject.

These phrases have the simplest structure. Since we don't have an object we just have a subject (an NP) and an intransitive verb.

We'll call the subject is the king of the phrase because it controls the verb. The verb endings will always line up with the king.

Check out the following examples. Click on the to see the structure of the phrase in blocks. Click on the to change the subject and see how the verb changes with it.

Notice how the subject never inflects. Whether it's past or present tense, the structure stays the same with these intransitive verbs. The subject doesn't inflect and the subject is king .

To review: with intransitive verbs (in all tenses):

- the subject

- is the king

- is not inflected

2. With non-past transitive verbs 🚲

Transitive verbs are verbs that take an object. For example, with the verbs:

- خوړل - khoRul (to eat)

- لیدل - leedul (to see)

- وهل - wahul (to hit)

These involve a subject that eats an object (something), sees on object (someone), or hits an object (something). For example, in the phrase زه توپ وهم - zu top wahum (I hit the ball), we have a subject (I), that hits an object (the ball).

The structure of VPs with transitive verbs that are not in the past tense looks like this:

We have a subject NP that we'll call the king of the phrase. It controls the verb, and it does not get inflected.

We also have an object NP that we'll call the servant of the phrase. When we learn about shortening VPs we'll learn more about what the servant role means, but for now we can just know that the king controls the verb endings, not the servant.

Go ahead and play around with these examples by pressing the and buttons. Notice how the subject and object do not inflect, and the verb always agrees with the subject . But here's where things will get a little weird... If you use a 1st or 2nd person pronoun as an object, it will inflect.

Any other kind of object will not inflect. It's just the 1st and 2nd person pronouns that get inflected. If this seems insane, there are actually a lot of languages that behave differently with 1st and 2nd person pronouns - after all they are a little more "personal" and so they behave different.

To review: with transitive verbs in non-past:

- the subject

- is the king

- is not the inflected

- the object

- is servant

- is not inflected, BUT 1st and 2nd person pronouns will inflect

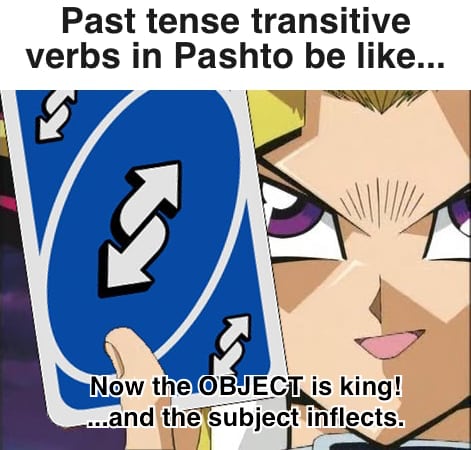

3. With past-tense transitive verbs 🚲🤪

This is where things start to get really weird. With past tense transitive verbs, the whole phrase structure seems to flip around. With these kinds of verbs the object is the king of the sentence and the verb agrees with it! 🤯

Look at this sentence for example:

The subject (the child) is the servant and the object (me) is the king ! For learners who aren't used to this new structure this can sound like "I hit the child", but no, this sentence means that The child hit me .

This kind of craziness where the verb lines up with the object is called ergativity and in Pashto it only happens in the past-tense which makes it a split ergative language. Yay. Because Pashto.

The other thing that happens in that the subject always inflects and the the object does NOT inflect.

Go ahead and play with the examples above. See if you can follow what's happening with the structure.

- The subject gets inflected

- The object does not inflect

- The verb agrees with the object

When you're first learning to understand and say sentences like this it can feel really awkward - almost like learning to ride a reverse bicycle. 🚲🤪 You'll probably make a lot of mistakes while speaking at first, but if you understand the weird new structure, with (lots of) time you'll get used to it and it will become automatic.

To review: with transitive verbs in past tense:

- the subject

- is the servant

- is inflected

- the object

- is the king

- is not inflected

Summary

Remember the analogy about learning to ride the reverse bicycle above? 🚲 Well with Pashto it's actually like learning to constantly jump between a reverse bicycle, a regular bicycle, and a scooter, because you have to keep changing the sentence structure based on what kind of verb you're using.

- Intransitive (Scooter 🛴)

- Non-past Transitive (Bicycle 🚲)

- Past-tense Transitive (Reverse Bicycle 🚲🤪)

Here's a little chart to summarize the three structures:

Switching between two opposite bicylces and a scooter is difficult for people learning to speak Pashto. It's very easy get these three structures mixed up. For instance, when people say a past tense sentence with an intransitive verb, they are often tempted to inflect the subject (because it's past tense) and will say something like ❌ ما هلته اوسېدل ❌ - ❌ maa halta osedeúl ❌ (I lived there). But this is wrong! It should be زه هلته اوسېدم - zu halta osedúm (I lived there) Make sure you understand the differences between these three different setups (intransitive, non-past transitive, past-tense transitive) and with practice you'll get used to using the right one at the right time.

Other Notes

Subject/Object Order

Usually people will say the subject before the object, but very often for emphasis or variety people will say object first, then subject. The word order isn't fixed like it is in English. Both of these sentences are correct.

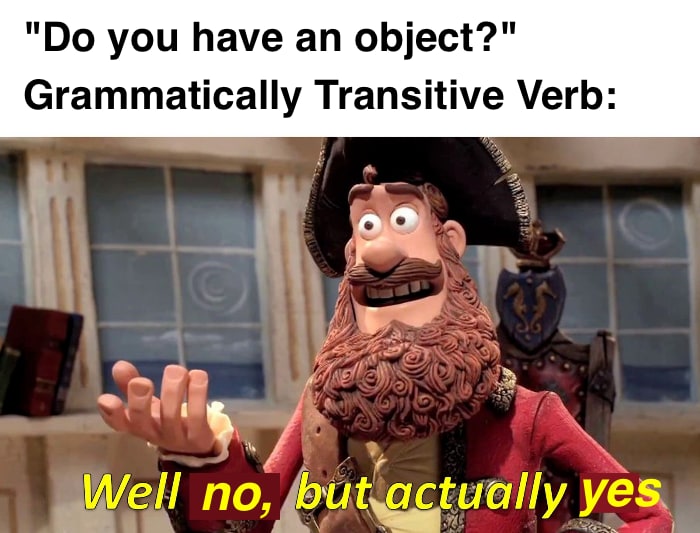

Grammatically Transitive Verbs

With some verbs transitive like اورېدل - awredul (to hear), کتل - katul (to look), لیدل - leedul (to see), لیکل - leekul (to write), you can talk about doing the action (hearing, seeing, looking, writing) without mentioning a specific object.

For example if you say "I looked towards you":

This is a transitive verb, but there's no spoken object in this phrase. There's just a subject (I) and a verb (looked) and then a AP explaining the direction that I looked. (Some people might talk about there being an indirect object but we will never use that term when talking about Pashto, because it's super confusing. In Pashto there can only be one object in a phrase, and it's just a direct object.)

Whenever this happens the object is considered to be 3rd person masculine plural. That's why the verb is conjugated as وکتل - óokatul. This is a past tense transitive sentence and the verb is agreeing with the unspoken, ambiguous 3rd pers. masc. plural object/king of the sentence.

This is most probably often seen in phrases like

Here we're using the transitive verb وایل - waayul (to say) but we don't have a specific object, so again, we pretend there's a 3rd pers. masc. plur. object that we're not mentioning.

Then, things get a little weirder because there are a number of verbs that don't seem verb transitive but they actually are used as transitive verbs in Pashto. We'll call these grammatically transitive verbs. Some really common ones are:

- خندل - khandul (to laugh)

- ژړل - jzaRul

- نڅل - natsul (to dance)

In Pashto, these verbs are transitive, and they use that same unspoken 3rd person masculine plural object. So we would say: